Friend & Colleagues remember M.F.K. Fisher

In their own words

Ruth Reichl on M.F.K. Fisher

Excerpt from The Browser

Ruth Reichl on American Food

Click here for full article

Why did people slavishly follow French cuisine?

I think it’s because if you go back to the roots of America, we were founded by Puritans who had no pleasure in food. There is an almost anti-epicurean tradition at the very base of America. For much of the middle part of American history, people who wanted to overcome that went to France. For me, what’s exciting about what is happening today in food is that we’re finally embracing America. We have become a food culture, but we very much were not. So you have someone like [Angelo] Pellegrini. I find him remarkable. His book was actually written the year I was born [1948]. He has what I now consider a modern American aesthetic of food. But people in America weren’t thinking like that in 1948. It was a culture of hamburgers and frozen food. The industrialisation of food was just about to start. And here you have this man saying, “Wait a minute! Why are you spending all this time on your lawns? Pull them up! Plant some food!”

Yes, I noticed the references to tinned or canned vegetables in some of the books you chose.

In the middle of the 20th century, that what’s American food was! Canned food, frozen food and then 10 years later you get the “I hate to cook” book. Then the women’s movement came in and there was a whole backlash against cooking. If you’re going to look for people who cared about food at that particular point, you have M.F.K. Fisher going to France and discovering food. She was brought up in a Quaker town.

Shall we start with her book then? You’ve chosen a collection of five of her shorter books called The Art of Eating. It’s part memoir, part musings on food.

M.F.K. Fisher was a wonder and a huge influence, and someone I got to know pretty well at the end of her life. She had this epiphany when she went as a young bride to France and discovered food – to me, in the best possible way – and brought that back to America. What I love about her is that she’s really a wonderful writer. She’s very thoughtful about the subject of food – it’s a subject that she embraces and takes on. For someone like me, growing up in the 1950s, if you wanted to read this kind of stuff about food, there wasn’t anybody else.

I read the chapter “Consider the Oyster” last night, from 1941. Were Americans generally not eating oysters at that time?

If you go back in American history, oysters were the food of poor people. New York was filled with oyster saloons in the 1800s. They were so abundant and so plentiful that we ate them all up – and they went from being the food of the poor to being almost impossible to find.

Although there are recipes in it, it’s not a cookbook is it?

No, it’s a book about taking pleasure in food.

How to Cook a Wolf

Krissy Clark, American Public Media, JULY 19, 2008

How much money are you going to spend feeding yourself this weekend? The average American spends about seven dollars a day on food. But as the economy slows, and food prices rise, that budget grows harder to maintain. The cost of food for a basic nutritious diet has gone up more than seven percent in the last year.

More families are turning to food stamps and food banks to get by. Americans are eating out less, and cutting coupons more.

It's enough to make the whole eating thing an anxiety-ridden affair, and that's not good news for digestion, or general well-being. What to do? Solace might be found in an old book.

The book is called "How to Cook a Wolf," but there were no real wolves harmed in its making. The wolf in question is the figurative kind, that comes sniffing at the door when times are tough, and food is hard to come by.

Author M.F.K. Fisher wrote "How to Cook a Wolf" in 1942, in the midst of World War II, just as food rationing programs were kicking into gear in the United States. Strict limits were put on basics like sugar, butter, meat, and coffee, and war-time slogans encouraged American households to "make do, or do without."

MEETING M.F.K. FISHER

by Leo Racicot

Some books (sadly very few) cast a magic over us, and over the time and place we read them, that lasts a lifetime. One such book for me, the memory of which even now resurrects a certain summer many summers ago, and the front porch I read it on, during what seemed to me the most beautiful of weather days, was "As They Were" by an author I had never heard of: M.F.K.Fisher. The title still has the ability to thrill.

I liked the book, in fact, so much that I set off, after, in search of another of the author's titles: "A Cordiall Water". I had no luck finding it (all library copies were marked 'MISSING'). The book was out-of-print and a friend suggested I write the publishers to see if a copy could be had from them.

A month or so after, a package, brown-bundled and tied with plain, brown twine came in the mail. It was from the author herself, accompanied by a note thanking me for my interest in her books with a wish that I enjoy this one. Thrilled, I dashed off a "thank you" straight away. She wrote back -- a longer, more personal reply, and so developed between us (me here in Lowell, Ma; she, in California) a regular correspondence that evolved into years of indescribable joy in visiting her, knowing her, loving her...

I can tell you many good stories about her and her open-door policy salon, her family and friends but will start here with the story of the first time I made my way, at her invitation, to her fabled Glen Ellen and 13935 Sonoma Highway because the first visit was a real adventure but not, as you will see, the sort I expected. The flight out to San Francisco was, as I recall, fine but I hit the city during one of the most relentless rainstorms to swallow Northern California in twenty years. Oh...my...God!!!

I can still picture being soaked to the skin as I wedged myself into an equally wet phone booth at the airport where I tried to summon the courage to call Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher and let her know I was here. I was more than nervous. The voice that answered the other end of the line was a shock and a delight, both, and remained so for all our days together, for what I heard emerging from a woman in her late 60s was the voice of a little girl, musical in its pitch, like little, silver bells ringing. "This is Mary Frances", it said. I said it was Leo calling and that I was in San Francisco and what I heard next was not what I wanted to hear: "Well, dear. I'm so happy you came but I'm afraid we are completely flooded up here. We needed the rain but not this much of it. The roads leading up here are all washed away. I'm sorry, dear, but you'll have to go back home. There's no way up. Maybe some other time..."

"Maybe some other time???" I was not hearing this!! I had come 3000 miles to be told, "Maybe some other time"?I heard her start to hang up and so I hollered, "No! Wait! I'll find a way. I want to see you. I've come all this way. I......I....." There was a pause, then the child-like voice replied, "Well, Leo, if you think you can get here, I'm here..."

No one at the bus terminal ticket booth knew Glen Ellen, the tiny cow town about 60 miles north of San Francisco where M.F.K. Fisher lived. They kept shrugging and sending me from booth to booth. I was mad. I was sad. I was wet. Good luck came in the form of a bus line, Fedora, no longer extant (nowadays, you must take an airporter limo to get to Glen Ellen, if you can get there at all). Feeling relief, I bought my ticket, found the bus dock and boarded a rattle-y, old coach bound for Santa Rosa. Much to my dismay, and perhaps due to the recluse in me, my delight, I saw that I was the only passenger on the bus. Or should I say the only person crazy enough to be riding a bus in weather this vile? And so we setoff into the deluge: one bus, one bus driver, one killer storm and me. Oh...my...God!!!

The further out of San Francisco we went, the more I could see what Fisher had meant; all roads were beyond-belief bad and the rain became more and more like an iron wall of water. We could not see very well but we could see that a major road had been washed away and that we were banned from continuing on by a battery of workhorses. During the ride, I had told the driver whom I was going to see and how determined and excited I was about seeing her. Pshawing the washed-out road, the driver became suddenly imbued with a do-or-die John Wayne spirit and grabbing the wheel with the hams of both hands, he yelled,(I kid you not!), "I'll get ya there, come Hell or High Water!!") and veered the giant bus into the middle of a mud-filled field as if he were re-directing a VW bug or a Cooper. Once again --Oh...my...God!!! I thought: I am not going to meet M.F.K. Fisher because I am going to die.

But the shortcut led to the highway we needed and soon we were back on pavement, at least, and not mud and before long, as if in a dream, the kindly driver was depositing me in front of the Jack London Lodge in the center of Glen Ellen. Eureka!!! It took me the whole night to dry off, and I don't think I slept an hour, if that. I was restless with all kinds of emotion not the least of which was shyness at having to call M.F. in the morning and actually meet a writer who had become, for me, the greatest living writer of all. I was a wreck when I dialed her up and heard her girl's voice again. "Well, I don't know how you managed to make it", she said, incredulously, "but I sure am glad you have. I'll send Pat Moran up in my jalopy to fetch you. He'll be round in an hour or so."

Pat arrived right on time, a cheerful, mustachioed,30-ish fellow, tall like a tree, and just as cheerful. We had a good chat as we made our way up and over some of the wettest country I had ever seen.

Soon, we came to a gate leading off Highway 12,to a path lined with wildflowers of every color and kind, flattened by the weight of the rain but oh, so fragrant, and a tiny, white bungalow, stucco, hidden carefully amid a clutch of trees, and a pond, and a belltower and cows, and oh it was lovely until, as we reached the house and parked, Pat turned and said to me, "How many times have you been out here to visit Mary Frances?" And when I told him this was the very first time, that I had never met her, he gasped asthmatically and said, "Holy Jesus! You must be SCARED SHIT!!!" This, I can tell you, did nothing to relieve my fear and once more, dear reader, if I may be permitted to repeat --- Oh...my...God!!!

But she, the Mary Frances of my dreams, was lovelier than words can describe and more warm and welcoming than the sun that had finally come out from hiding. The years ahead would be filled with the rich and endearing gift of her friendship, her letters, her love. Not a day goes by that I do not miss her and wish she was here and I think, in some animistic way, she still is, and surely is with me now as I write this reminiscence of the first time we met.

True Confessions

The July 2008 issue of Gourmet magazine featured this article on M. F. K. Fisher in celebration of her 100th birthday, July 3, by Dame Jeannette Ferrary of the San Francisco Dames chapter. It is an up-close look at her very private world. Dame Ferrary knew the Grande Dame personally for 15 years and wrote the biography M. F. K. Fisher and Me: A Memoir of Food and Friendship.

Originally Published July 2008, Gourmet Magazine

This month marks the 100th birthday of M. F. K. Fisher, whose sensuous, evocative prose redefined food writing. Here, an exclusive, up-close look at her very private world.

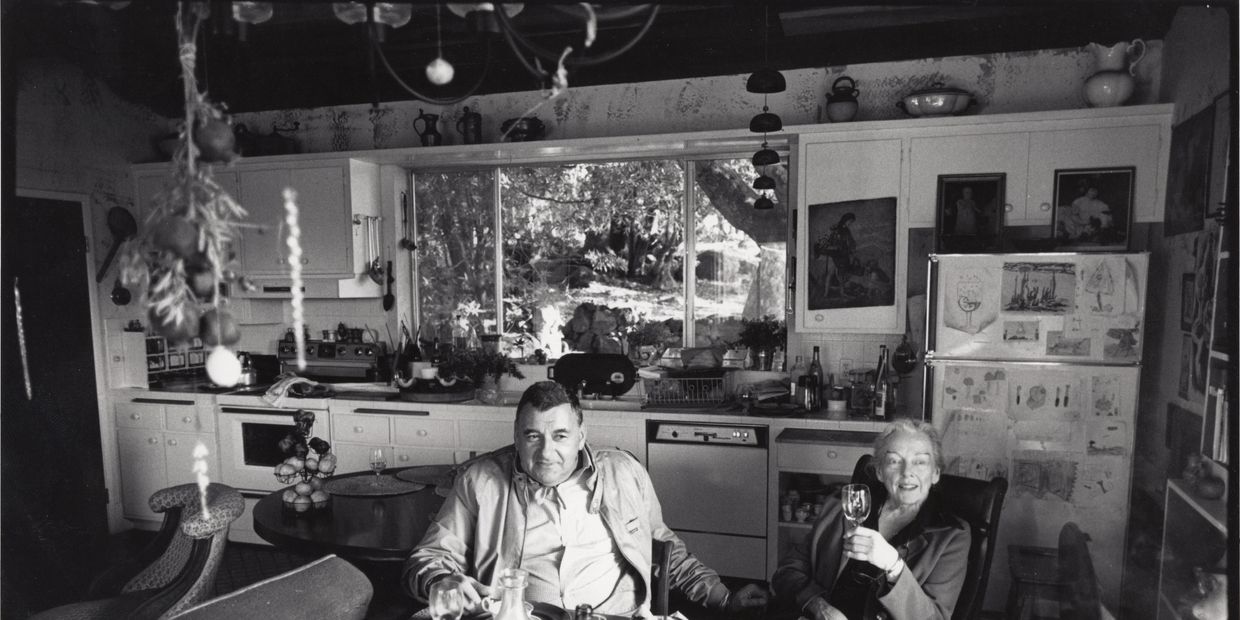

The art of eating: M. F. K. Fisher’s culinary landscape stretched from the cafés of Provence to her kitchen at Last House, in Sonoma Valley.

It really didn’t look like much. The untitled book had a well-worn black cover and some clippings sticking out here and there. Inside, in scrabbly handwriting, I found the words Table Book, and as I slowly turned the pages, I began to realize the importance of this collection: Arranged by date, they were M. F. K. Fisher’s unexpurgated notes on those who’d come to visit, the food she’d served, the reactions of her guests, and her own reactions to them. The book had been at the bottom of a carton of gleanings from Fisher that had been sitting on my floor for weeks. One day (a few years before she died) she’d asked me to go through her library and take whatever I wanted, so I packed up a few boxes without looking too closely at things.

Now, I’d finally cleared my own overburdened bookshelves to make room for Fisher’s trove. I looked again at the book in my hands. From her first published work, in 1937, to her last volume of memoirs, published posthumously in 1995, Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher insisted on good, honest food and good, honest writing. That said, she was also famously cryptic and charmingly enigmatic. This book might well have been her only confidant. I sat down immediately and began to read.

“PC a food addict,” Fisher noted in June 1965. He “stopped before dessert—claimed it was the first thing he had eaten for 2 weeks, except bread & water. He is very imitative—limited intelligence but brash.” Another guest “arrives stoned from party—late—no apologies.” Another had the “taste buds of an ostrich.” She was particularly adroit at the art of damning with faint praise. Of lunch with food writer James Villas, she notes, he “ate nothing—hungover? OK interview? Pleasant non-encounter—near miss.” But she also needed only a few words—“Provençal, lush, beautiful”—for a much enjoyed afternoon with Alice Waters and friends. For measuring success, Fisher invoked the classic standard of her friend James Beard: “It was a nice party. Nobody cried. Nobody threw up.”

Nothing seemed to annoy Fisher like fussiness. “Miss E. cannot eat a dozen things … because of a recurrent pain in the gall bladder, or she cannot chew them w/ her double clickers or she is prejudiced against them for unknown but probably racial reasons.” And, if fussiness was reprehensible, nonfussiness was even more irksome: “They will eat anything that is set before them,” she writes of two dinner guests. “They chomp right through, making appreciative noises on schedule.”

But whatever her criticisms of others, sometimes she turned her unflinching eye upon herself—and for good reason, since one year she almost poisoned her entire family at Christmas. “You are now entering tomane [sic] junction,” she wrote of the near-disastrous meal. “In my unreasonable desire to have everything culinary well under control, so that we could all sit around and talk and enjoy the baby and so on … I had blandly advised Bill to stuff the turkey at night, and roast it the next morning. I knew better. I was not thinking. This was dangerous enough, with quantities of raw oysters chopped in the warm dressing and packed into the very perishable carcass, and to compound my idiocy the weather turned very balmy during the night the bird sat on the back porch. A perfect prescription for … mass murder… ” She even imagined a headline: “Noted Gourmet Does In Family.”

Occasionally, Fisher included specifics about how she prepared a dish, as well as any shortcuts she had taken. She seemed to enjoy the fact that no one would ever think her capable of resorting to such “tricks,” because she was, after all, M. F. K. Fisher. “I followed the Rombauer recipe pretty well. Then I added two cans of Campbell’s Cream of Potato, which has the potatoes in little cubes … and as I added the pre-cooked asparagus tips I added about a half-cup of chopped parsely [sic] … all to add to the too-delicate flavor and make it look greener. Excellent! A lowdown trick, but worth it.”

Pouring over every menu and marginal note in the book, I eventually worked my way through to October 3, 1977, the date of my very first visit with Fisher. Through squinted, reluctant eyes, I read the menu: “Wafers, chermoula, rolls, salad, lettuce, h.b. eggs, prawns, ww [white wine], coffee, shortbread.” So far, so good. “Very pleasant long lunch, interesting people.” Well, not overly enthusiastic, perhaps, but not too awful. On the other hand, I wonder what she meant by “long”?

Passion

Cyra McFadden, San Francisco Examiner

"Food is what she wrote about, although to leave it at that is reductionist in the extreme. What she really wrote about was the passion, the importance of living boldly instead of cautiously; oh, what scorn she had for timid eaters, timid lovers, people who took timid stands, or none at all, on matters of principle."

Waxing Eloquent

James Mustich, Jr.

M. F. K. Fisher is one of the writers I most admire, and one of the essays contained in With Bold Knife & Fork, "Once a Tramp, Always . . .", may be my favorite piece of her prose. It is about craving, the dizzying meeting-place of hunger, gluttony, and enjoyment.

In the course of ten pages, Fisher waxes eloquent about caviar and potato chips, about real mayonnaise and its awful substitutes, about childhood and - no kidding - mashed potatoes with catsup. There are sixteen other casual assaults on culinary enthusiasms gathered in this copious volume, and the targets range from soup to nuts, from eggs to innards, from bread to pickles; they're all hit, held, and caressed by sentences aimed with sharp vision and sure affection.

Remembering Mrs. Friede (M.F.K. Fisher)

Anita Monroy Peters

It was September 1954, the first day of school at St. Helena Elementary School. I was starting 6th grade and Anne K. Friede was one of the new girls in school, starting the 5th grade.

I befriended Anne in the schoolyard and was delighted to find out she had moved to a house up the road from my house. We made plans for me to come over and play.

Anne invited me into her home up the road which was nestled under tall oak and redwood trees. Baskets of oranges and apples adorned the back porch. I entered to meet a very tall woman standing in the kitchen dressed in a long beautiful and colorful flowing gown with a shawl around her shoulders. Her hair was pulled back with two big black shiny sticks poked through the bun at the nape of her neck. My friend's mother was much more interesting than my friend.

I didn't have time to be startled at this very different looking mom, because I couldn't take my eyes off of her lips, her red lipstick, her sweet smile and her kind eyes looking down at me. She told me she wanted to thank me for being so nice to her daughter at school. Please sit down, she said, you are Anne's first friend in St. Helena. I have made lunch to celebrate. Well, in all my eleven years, this was the first time I was spoken to as an adult, and made to feel like a very important one.

To this day, I remember what she served for lunch. Carrot and celery sticks, piled high in a plate and little tiny pickles. I saw her slicing the meat for the sandwiches. I gulped when I saw the huge piece of raw meat. She put thin slices of this raw meat on bread with mayonnaise, lettuce, tomatoes and mustard. Being polite, I just swallowed the pieces of the raw meat whole, as best I could, without choking. I was the guest of honor and the most important person there and I certainly wasn't going to hurt her feelings by telling her meat has to be cooked first. Being served my first rare roast beef sandwich was unfortunately not appreciated by me.

After lunch, Mrs. Friede excused herself saying she had to go to work, and would we like to play records while she worked in the next room. Anne and I listened to show tunes from musicals and Spike Jones. I looked around the room and saw a painting of a woman that kind of looked like a mermaid on the beach surrounded by shells and starfish. Anne said, "That's my mother. She was painted by my father". I looked at the painting again. She was nude! I was shocked! I was eleven.

I heard typing in the next room. I asked Anne what kind of work did her mother do. Anne said she was a writer. What does she write? She writes books. What books had she written. She showed me a small cloth bound green book. The title was "How To Cook A Wolf." I was brought up never to say unkind things, but I thought, who would buy such a book. Who would want to cook wolves and where would you find one! She doesn't know enough to cook meat before serving it, now she's cooking wolves!

Mrs. Friede floated into the room where Anne and I were playing records and said it's nice and warm outside, let's go make vanilla ice cream for dessert. The four of us took turns cranking the handle on the ice-cream maker. She sprinkled chocolate shavings on top of each mound of the best vanilla ice-cream I had ever tasted.

I skipped home that afternoon reflecting on how I had just met the most different and most interesting person of my short life. I would enjoy almost 10 more years of friendship with Anne, Mary and their mother. As I grew older, I gravitated toward and enjoyed their lifestyle which was so different from my own family. I was invited to many gatherings at her homes in the valley. Mrs. Friede always received me in the same manner that she received her adult guests. She always made it a point to introduce me by saying, this is my good friend, Anita.

Thank-you for giving me this opportunity to remember a great lady. I miss her.

A Special Dinner

Karen Berman from The Art of Writing About Eating.

M.F.K. Fisher's Lifetime of Food for the Soul

In honor of M.F.K.'s 70th birthday she had a special dinner at Chez Panisse in which each course was composed around the titles of her books:

the first course, Consider the Oyster, inspired a selection of four varieties of oysters on the half shell

A Considerable Town featured California snails with Pernod, tomatoes and garlic, followed by whole Pacific rockfish charcoal-grilled with wild herbs and anchovies, young spit-roasted pheasant with new potatoes, a bitter lettuce salad with goat cheese croutons, and three plum sherbets with orange rind boats

A Cordial Water suggested the last course, a Muscat de Beaumes-de-Venise, coffee and candies.

Frances Kennedy Fisher is widely acknowledged as the creator of the genre we now call "food writing." She was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters and received lifetime achievement awards from the James Beard Foundation and the American Institute of Wine and Food

At the beginning of The Gastronomical me, Fisher explained herself: "People ask me: Why do you write about food, and eating and drinking? Why don't you write about the struggle for power and security, about love, the way others do?. . . The easiest answer is to say that, like most other humans, I am hungry. But there is more than that. It seems to me that our three basic needs for food and security and love, are so mixed and mingled and entwined that we cannot straightly think of one without the others. So it happens that when I write of hunger, I am really writing about love and the hunger for it. . . There is communion of more than our bodies when bread is broken and wine drunk."

M.F.K. Fisher Commemorative Dinner

Another example of quotes made for an M.F.K. Fisher Commemorative Dinner, Southgate Cafe,

October 25, 1997

Hors d'Oeuvre: With Bold Knife and Fork

"I am too young and of course of the wrong sex to remember the fabulous Free Lunches of the old-time saloons, but the display of hot and cold appetizers I have observed lately in the City is impressive to my naive eyes."

Terrine and Country Pate: With Bold Knife and Fork

"Often in France I have used a rather ruthless gauge of a restaurant's worth, no matter what its class or reputation, by ordering a portion of the 'pate maison,' and as is often the case in other fields, I have found some of the best in the most unpretentious eating places."

Pumpkin Soup: With Bold Knife and Fork

There is excitement and real satisfaction in making an artful good soup from things usually tossed away."

Poached Brook Trout with Salmon Mousse: The Gastronomical Me

"I tasted the last sweet nugget of trout, the one nearest the blued tail...Fate could not harm me, I remembered winily, for I had indeed dined today, and dined well. Now for a leaf of crip salad".

Mesclun Salad: Alphabet for Gourmets

In a perfect meal "there is a large but bland green salad ('to scour the maw,' Rabelais would say), made with a minimum of good white wine."

Apple Tart: Long Ago in France

"Then he would peel apples from Normandy, and cut them into thin, even half-moons, and toss them in a bowl of white wine. . . beat eggs and cream and nutmeg into a custard, and fill the shallow crust half full. He took the apple slices from the bowl one by one, almost faster than we could see. . . and laid them in a great, beautiful whorl, from the outside to the center, as perfect as a snail shell. He did it as effortlessly as a spider spins a web."

Cheese: Alphabet for Gourmets

"Bread stays on the table for the next course of a hand-count of cheeses on a board: buttery Gorgonzola, Camembert 'more running than standing,' impeccable Gruyeres, Cheddar with a bite and crumbling to it, and double-cream as soothing as a baby's fingertip."

John Thorne, the creator of the food letter, Simple Food, has agreed to allow us to quote from his tribute to M.F.K. Fisher. "Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher handled these things differently. She possessed an equally fine sensibility but sported it in an offhand, very American way. Hers was the pose of the maverick.

"I'm not a writer," she would insist the moment she felt you were about to treat her like one. She was just as impatient with culinary pretension. "I know red from white and I think I know good from bad and I know the phonies from the real, and that's about it," she once told food writer Ruth Reichl. To get through to her, you had to be fearlessly honest. If she felt you waver, she would quickly bat you to one side.

The point, however, is that you could get through, and her writing actually encouraged you to try. The clever asides, the dismissive gestures, the sly ironic glances -- a pose is struck and a quick look is thrown your way to see if you've been taken in by it -- all these make up a style that is intimately conversational. It insists that you lean across the table and listen close. The effect is that of a letter from a difficult but compulsively fascinating friend."

On Being Married to M.F.K. Fisher

Text by Donald Friede 1

I very much doubt if my mother will ever believe that we lived on anything except tenderly poached pheasant’s breasts garnished with truffles, and followed by a mousse of chestnuts, flavored with Kirsch and topped with whipped cream. I am sure that she visualizes perfectly chilled Rhine wines and Champagnes, varied with an occasional bottle of very superior Burgundy, as the accompaniment to our every meal. And the icebox, in her mind’s eye, is always stocked with luscious roast chickens and cold roast beef and pâtés and delicately trembling aspics. As a matter of fact I am convinced that her view is shared by all of my friends who have not actually stayed with us or visited us. And I suppose that I must have had the same general picture of what our gastronomical world is like.

It is perfectly true that when we manage to make the necessary arrangements about sitters and such, and do go down to Hollywood for a day or two, we luxuriate in the Haute Cuisine of Romanoff’s or Perini’s. And our favorite dinner of Oysters and Sauvignon Blanc, Squab Vert Pré and Pinot Noir - with an extra order of watercress - and the best available cheese and bread and coffee and a really good Biscuit Débouchet, is not exactly Spartan fare. But that is as occasion meal, and treated as such, and looked forward to and remembered with mouth-watering pleasure. Between times we live more simply. There may not be haunches of venison available for midnight suppers, but somehow they are not missed. For one thing midnight snacks are not part of a life which includes two young children and a never-ending series of deadlines. And for another - but it might be simpler to tell just what we do eat.

Our one point of difference gastronomically is breakfast. To me that first meal of the day is an almost obligatory sequence of fruit-eggs-toast-coffee - with the only desirable variations being the actual elements themselves. MF (Mary Frances) feels that breakfast is not so much a meal as a preamble to the day ahead. On this very sound theory she may drink a glass of vermouth and eat a toasted muffin, or she may decide that what she wants is a plate of hot buttered zucchini. I have seen her start the day with a cold leg of Mallard duck, carefully set aside the previous evening for that particular purpose, and a glass of wine. But usually she will drink a cup of tea or a tall glass of hot café-au-lait. And once she paid me the compliment of accepting one of my poached eggs. But on the principle that each man chooses his own poison we go our own ways at breakfast. The unpredictability of MF’s first meal of the day is only matched by the complete predictability of mine.

But from this point on there is complete agreement on the joys of simple meals using the fresh ingredients which we can buy in our local store and limited usually to one main dish. And why shouldn’t there be? You are not very likely to argue if you know that you will sit down to a lunch of lentil soup, with savory traces of onion and tomatoes and bay-leaves and bits of smoked sausage and toasted sour dough bread both flavored by and flavoring the soup served piping hot. Or it may be a salad of crisp romaine or tender lettuce, with anchovies to add to the pleasures of the dressing, and with the grains of fresh ground pepper adding their own inimitable touch. And the wicker breadbasket with its napkin hiding the contents will as likely as not prove to be filled with fluffy biscuits baked with Parmesan cheese. Again it may be a freshly tossed bowl of chopped chicory with bits of crisp bacon in the olive oil-vinegar-garlic salt and ground pepper dressing. Or an equally tempting vegetable salad, or cucumbers and sour cream, or cold roast leg of lamb with a tart salad of beets and onions. And always beautiful cold fruit and grapes, or a big slab of cheese and toasted bread and crackers. We work in the afternoons, and so rarely drink anything before sundown. But we may have a glass or vermouth, or of chilled Gray Riesling, or even a glass of our favorite Red Tipo. And sometimes, when it is cold and rainy, we will have hot aromatic tea, cup after delicious cup of it.

We do all right for dinner too. Occasionally we may start with soup, a rich stock aromatic with pureed tomato and spices and into which we put heaping spoonfuls of sour cream. Or it may be flavored with clam juice or oyster sauce or minced clams. But usually we do not have any soup at all. We find that is detracts from the enjoyment of the rest of the meal. Often our dinners will consist of Tartar Steaks, pink and exciting, made from round steak from which the last vestige of fat has been carefully removed before it is run once only through the grinder. The raw egg-yolk lies unbroken in the depression in the center of the meat, and there is a platter of crisp watercress or of slivers of tomato and onion, without any dressing whatsoever, on the table. And toasted sour dough bread, and no sauces or capers or fancy condiments, only a saltshaker and a pepper mill.

Or it may be a ragout of beef, which has been simmering in the soup pot for a day or so, filling the house with a gentle and exciting aroma. Or lamb chops, moist and succulent, prepared in a heavy iron pan on top of the stove so that the juices will all be there waiting for the addition of butter which will blend them into a rich natural gravy. Or a curry, each grain of the brown rice separate and delicious, and the tang of spices inextricably interwoven in the meat and the sauce. Or a steak, thick and aged, marinated in soy sauce for hours, broiled over charcoal embers on a barbecue in the patio, and basted with chopped herbs and onions which have been added to gently simmering butter to which, in turn, has been added red wine. Watercress, tomatoes and onions, parsley - these are all we serve with the steak. And afterwards a ripe Liederkranz or Camembert. And Coffee - black, strong, and preferably bitter with chicory.

Often we do not have any meat at all. There will be a casserole of spinach flavored with mushrooms and cream, or zucchini with the grated cheese crisp and brown on top, or cauliflower Polonaise with the bread crumbs brown in the hot butter, or blini with melted butter and sour cream, or spaghetti al dente, with a bowl of grated Parmesan, and butter sauce, and crisp leaves of romaine to munch on. Or a Risotto, zesty with saffron and dried mushrooms, and garlic bread and a bowl of poached peaches or apricots.

And always there are nameless dishes, made of leftover peas or carrots or steak or rice or baked potatoes which come to the table twice as delicious, if that were possible, as they were in their original form. They are more tasted into being than cooked. To my mind they are the perfect example of the triumph of an imaginative palate over the precise pages of a cookbook. It is an old family joke that MF’s father once warned her sister not to leave any remnants of a certain dish exposed to view. "MF will make something of it if you do," he said. He might well have added that whatever she made would be delicious.

As for the rare old vintages with which we wash down our meals - they too simply do not exist. There is a carafe of red wine on our table, filled with a simple discreet wine which we buy by the gallon in the local liquor store. Occasionally there may be a bottle of chilled dry white wine. And always there is a quart bottle of good beer in the icebox.

And yet, maybe mother is right after all.

Commentary by Joan Reardon

After Donald Friede’s death in 1965, his widow, Eleanor Kask Friede, found an item among his papers that she thought his former wife M.F.K. Fisher would like to have. Written about twenty years earlier, "On Being Married to M.F.K. Fisher" may well have been a pitch for an article destined for Esquire, or the beginning of a much longer piece that was never written, or simply an answer to a question that might have been posed by Friede’s widowed mother.

Although its destination was unknown, the typescript, found in a private collection of Fisher manuscripts, has added further definition to a writer who had introduced readers to a mélange of "secret indulgences": to tangerines toasted on the radiator and then placed in the snow on a window sill to turn as brittle "as one layer of enamel on a Chinese bowl", .2 to a raw oyster at The Bishop’s School in La Jolla, when with her first swallow she "felt light and attractive and daring, to know what I had done"; .3 to "one of the best meals we ever ate" when she, her younger sister, Anne, and her father stopped for water on the way from her aunt’s ranch in Valyermo to Whittier: "It was a big round peach pie…with lots of juices, and ripe peaches picked that noon." They spooned thick cream from an old-fashioned quart Mason jar over it, and "I saw food as something beautiful to be shared with people instead of as a thrice-daily necessity." .4

In what can only be described as an insider’s view, Fisher’s third husband, Donald Friede, turns the tables on his celebrated wife and shares the pleasures of her table with us. Granted that his is an admiring voice: "Nine years ago I read and fell in love with a book, Serve It Forth, by M.F.K. Fisher," he wrote in a paragraph that he later discarded. "In the then gastronomic wilds of Hollywood it was a reminder of fine food enjoyed in almost every part of the world, and of what the pleasures of the table could be. I chose to believe that I alone had discovered the book, and I made sure of the fact that none of my friends missed reading it. Many years later I met and married M.F.K. Fisher and we came to live on a mountainside at the edge of the desert in California." And, probably more to the point, Donald Friede’s voice was also the voice of a man who proposed marriage, courted, and wed his fifth wife in less than two weeks. He was a sophisticated man of the world, a connoisseur of women, wine, and food as well as a publishing giant and aspiring writer.

Although American-born, Donald Friede was raised in Europe, where his father was the Ford agent for Russia. He spent his freshman year at Yale in 1919, and his sophomore year at Princeton, and then we went off to make his fortune in a succession of short-lived jobs before he found his niche in publishing. His first job was as a stockroom clerk at Knopf, and then, using some inherited money, he became First Vice-President of the publishing house of Boni & Liveright at the age of twenty-five. He also dabbled in the theater and promoted a production of Antheil’s Ballet Mécanique. After that money-losing venture, he joined forces with ex-Chicago bookman Pat Covici.

The meteoric team of Covici-Friede published the Nobel Prize winners John Steinbeck and François Mauriac, as well as controversial novels like Radclyffe Hall’s Well of Loneliness and Theodore Dreiser’sAn American Tragedy. As a prototypical New Yorker during the Roaring Twenties, Friede traveled, wined, dined, gambled, and played with the best of the reluctant-to-grow-up generation. When the Depression forced the closure of Covici-Friede, he became a story editor for the A. & S. Lyons Agency, lived for the most part in hotels, drifted from the Plaza to the Ritz, and then he met Fisher.

The year was 1945, the place New York City. It was early May, the trees were in bloom, and the city was vibrant with victory celebrations since Germany’s unconditional surrender on May 7. M.F.K. Fisher had just arrived in the city with her twenty-month-old daughter, Anne, and nanny to take up residence in Gloria Stuart’s vacant apartment for an indefinite period of time, seeking refuge from the accumulated burdens of her second husband’s suicide in 1941, her brother’s death a year later, and a short-lived stint as a scriptwriter in Hollywood. The second night after her arrival, the author Kyle Crichton and his wife invited Fisher to a dinner party in the Village. Also a guest, Donald Friede, reintroduced himself to Fisher, claiming that he had met her earlier at a cocktail party in Hollywood.

On May 21, 1945, Fisher telegraphed her parents from Atlantic City: "AM IN A DAZE OF AMUSEMENT EXCITEMENT HAPPINESS BECAUSE I ACCIDENTALLY GOT MARRIED SATURDAY TO DONALD FRIEDE." Returning to New York, the Friedes sublet MacKinley Kantor’s duplex in Greenwich Village for the months of June, July, and August. Donald Friede played flamboyance to Fisher’s instinctive reserve, spendthrift to her financial caution. He broke her existing contracts, signed her on with his former partner Pat Covici, introduced her to her future agent Henry Volkening, and negotiated a contract for a book about feasting, a collection of excerpts from literature concerned with man’s fundamental need to celebrate the high points of life by eating and drinking. By the end of the summer, Friede proposed that they return to Bareacres, the home that Fisher had shared with Dillwyn Parrish in Hemet, California, where Friede believed that they could both write without the distractions of the city.

By September the Friedes were in residence in a remote house on a barren hillside overlooking the desert valley. Once an old cement porch facing Mount San Jacinto, Fisher’s remodeled kitchen was enclosed with ample windows and a floor covered with patterned linoleum. Clean and minimal, its furnishings included a white porcelain sink, stove, icebox, and a few counters, shelves, and bins. A Dutch door opened onto a patio of flat stones, an ideal place for outdoor dining and entertaining. In due time a second daughter, Kennedy, was born prematurely on March 12, 1946, and she occupied the high chair that Anne had vacated. There were daily rounds of chopped green beans, poached pears, whole-wheat crackers spread with sweet butter, and milk for the children. From her kitchen, "Fisher ruled" and loved the feeling. But after a day of cooking and writing she changed into a kimono and enjoyed a glass or two of Sherry with her husband - "one of the pleasantest minutes in all the 1440" - before the simple meal they shared. Or was it simple?

The lessons that Fisher had learned in her first kitchen in Dijon in 1930, namely that she wanted her guests to forget "home" and all it stood for during the few hours when they were at her house, had become a basis for her cuisine personnelle. She made it a priority to cook meals that would shake diners from their routines, not only of meat-potatoes-gravy, but also of thought and behavior. She devised entrees consisting of a potato or cauliflower casserole, a grilled steak or fresh mushrooms baked in heavy cream. Then she served a fresh salad or marinated green beans, peppers, and endive. These early menus translated into an American idiom in subsequent kitchens in Laguna Beach and Eagle Park and into her short-lived period of cosmopolitan entertaining with Dillwyn Parrish, at Le Paquis in Vevey. In spring she served guests the first crop of peas, shelled, quickly blanched, and dressed with only a bit of fresh butter; in summer she thickened fresh fruit in its own syrup; and in autumn she prepared stews of vegetables. And when she and Parrish returned to the States and settled at Bareacres, her simple but distinctive culinary style distinguished their dining and entertaining.

A period of living alone in a one-room studio apartment in Hollywood and the constraints of caring for her daughter and often cooking a solitary meal for herself, however, added an element of eclecticism to Fisher’s cooking style. And this is what Donald Friede soon discovered and described. Fisher’s "nameless dishes" concocted from leftovers appeared at the table in a more delicious state than the one in which they were originally served. They were a tribute to her educated palate and ingenuity, as was the first meal of the day. While Donald Friede never departed from his fruit-eggs-toast-coffee routine established during his years of hotel, restaurant, and business breakfasts, Fisher viewed the first meal of the day as a "preamble." A glass of vermouth, a heel-tap of last evening’s wine, a lamb chop carefully set aside or a plate of hot, buttered, grated zucchini were often as fanciful as the essay on dining alone or seducing a lover that she might write before lunch.

While the outlines of M.F.K. Fisher’s life are well-known from her first book (Serve It Forth, published in 1937) to her last (Last House, published posthumously in 1995), her three husbands have been relegated to either romantic shadows or vaguely realized mistakes. This despite the fact that all of them had the insight and ability to write volumes about the woman who has drawn readers into a magical circle of unforgettable family members, and into a cosmopolitan world of French landladies and winemakers, restaurateurs and waiters, academic friends, and scary street people. Fisher’s first husband, the poet and professor Alfred Young Fisher, only obliquely referred to his separation from his wife in a sonnet: "Those who once loved have, by mutation come/ to find themselves unrecognizable."5

Dillwyn Parrish, Fisher’s second husband and an artist, painted the back of her shoulders and head but never attempted a portrait of her face. And her third husband, Donald Friede, left this short, but no less perceptive, appreciation. "On Being Married to M.F.K. Fisher" adds another insight. Although Fisher’s marriage to Donald Fried ended in a divorce that he didn’t want but she felt was necessary, their brief life together with a memorable feast.

Notes

- From private collection. Reprinted with permission from Kennedy Friede Golden.

- M.F.K. Fisher, "Borderland," in Serve It Forth (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1989), 32

- M.F.K. Fisher, "The First Oyster," in The Gastronomical Me (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1989), 27

- M.F.K. Fisher, "A thing Shared," in The Gastronomical Me (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1989, 7

- Alfred Young Fisher, from Northampton Sequence: 1937 [unpublished ms.], Smith College Archives.

Learn more

Interested in reading more about M.F.K. Fisher? Consider reading one of the many books written about her life.

SIGN UP TO RECEIVE OUR NEWSLETTER

Sign up to receive the latest news and information from the M.F.K. Fisher Literary Trust.